55th Anniversary of the AWA

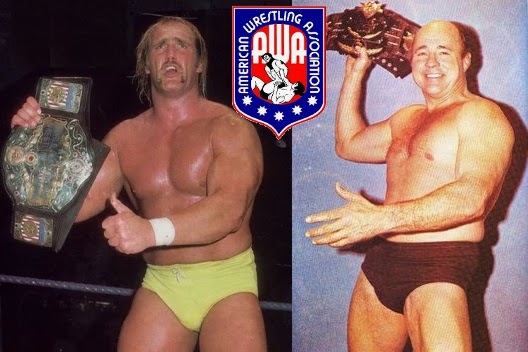

Two weeks ago was the 55th anniversary of the birth of the AWA, American Wrestling Association, which was founded in August of 1960.

The anniversary came less than four months after the death of its owner, and its perennial world champion until the final decade of its existence, Verne Gagne.

The anniversary came less than four months after the death of its owner, and its perennial world champion until the final decade of its existence, Verne Gagne.

Gagne, who passed away at the age of 89 on 4/27, was the most popular young babyface wrestler in the country during the early days of television.

In 1959 Gagne purchased controlling interest in the Minneapolis Boxing and Wrestling Club. Gagne, who was a member of the National Wrestling Alliance, was being constantly passed over for the World Title due to issues from years earlier.

It all started when NWA President Sam Muchnick booked Lou Thesz in Chicago for a date with a rival promoter. This upset the Chicago lead booker Fred Kohler, who responded by no longer booking the world champion. In his place, he created the United States TV championship. Gagne was named the first champion in September, 1953.

Gagne was the most popular wrestler in Kohler’s stable, and also, like Thesz, a very legitimate wrestler. He was the obvious choice to be champion. While double-crosses were almost gone by that time, promoters still felt it was safer to have their world champion be someone who could actually wrestle in case a rogue promoter or wrestler wanted to make a reputation on a national star.

In 1959 Gagne purchased controlling interest in the Minneapolis Boxing and Wrestling Club. Gagne, who was a member of the National Wrestling Alliance, was being constantly passed over for the World Title due to issues from years earlier.

It all started when NWA President Sam Muchnick booked Lou Thesz in Chicago for a date with a rival promoter. This upset the Chicago lead booker Fred Kohler, who responded by no longer booking the world champion. In his place, he created the United States TV championship. Gagne was named the first champion in September, 1953.

Gagne was the most popular wrestler in Kohler’s stable, and also, like Thesz, a very legitimate wrestler. He was the obvious choice to be champion. While double-crosses were almost gone by that time, promoters still felt it was safer to have their world champion be someone who could actually wrestle in case a rogue promoter or wrestler wanted to make a reputation on a national star.

Gagne and Thesz had wrestled all over the country in NWA world title matches starting in late 1950 in Texas, and with both being national stars off television, they took their matches all over the country. Thesz never beat Gagne. Early on, they would go to 60 minute draws as a way to protect the value of both the heavyweight and the junior heavyweight titles.

But Gagne being given the U.S. TV title changed everything.

Kohler no longer used Thesz, so while he was the world champion and did appear on television all over the country, he was not on the most popular show. Gagne was the champion on that show, and Kohler booked his champion similarly to how Muchnick booked Thesz.

To get Gagne, Fred Kohler Enterprises would get ten percent of the live gate, actually slightly undercutting the 13 percent that the NWA was charging. Many promoters booked Gagne instead of Thesz, since he had become more popular since he was the top babyface on the most-watched television show.

Once Gagne became champion, he never received another NWA title match.

But Gagne being given the U.S. TV title changed everything.

Kohler no longer used Thesz, so while he was the world champion and did appear on television all over the country, he was not on the most popular show. Gagne was the champion on that show, and Kohler booked his champion similarly to how Muchnick booked Thesz.

To get Gagne, Fred Kohler Enterprises would get ten percent of the live gate, actually slightly undercutting the 13 percent that the NWA was charging. Many promoters booked Gagne instead of Thesz, since he had become more popular since he was the top babyface on the most-watched television show.

Once Gagne became champion, he never received another NWA title match.

The feeling at the time is that Gagne wanted the title, and if they had given him the title, there probably would not have been an AWA. In May of 1960, it was announced on Minneapolis television that O’Connor had refused to defend the title against Gagne, the local star and the No.1 contender. It was noted that despite being one of the biggest stars in wrestling, Gagne had not received an NWA world title shot since 1953. So they claimed that if O’Connor didn’t sign for a match with Gagne within 90 days, he would forfeit the title and Gagne would be named champion.

Of course this wasn’t said anywhere outside the reaches of the local Minneapolis television show. Gagne had already decided to leave the NWA when the announcement was made, and that was just his angle to explain making himself champion in his local market, and when the AWA started, it was just a promotion that ran in Minnesota and North Dakota.

Of course this wasn’t said anywhere outside the reaches of the local Minneapolis television show. Gagne had already decided to leave the NWA when the announcement was made, and that was just his angle to explain making himself champion in his local market, and when the AWA started, it was just a promotion that ran in Minnesota and North Dakota.

On August 16, 1960, the 90 days were up. And it was announced that Gagne was the new American Wrestling Association world heavyweight champion. The AWA’s first card was that night in Minneapolis, at the Auditorium, before 6,213 fans.

It was not a great first night, as the ring broke during the main event and the show had to be stopped. It was a four-match show. The AWA was known for the next two decades for running major cities with fewer matches than most of the other major promotions, but giving the matches more time.

Largely forgotten is the role the AWA played in the creation of the so-called “big three” world champions, the NWA, AWA and WWWF, from 1968 until the AWA started fading in the mid-80.

It was not a great first night, as the ring broke during the main event and the show had to be stopped. It was a four-match show. The AWA was known for the next two decades for running major cities with fewer matches than most of the other major promotions, but giving the matches more time.

Largely forgotten is the role the AWA played in the creation of the so-called “big three” world champions, the NWA, AWA and WWWF, from 1968 until the AWA started fading in the mid-80.

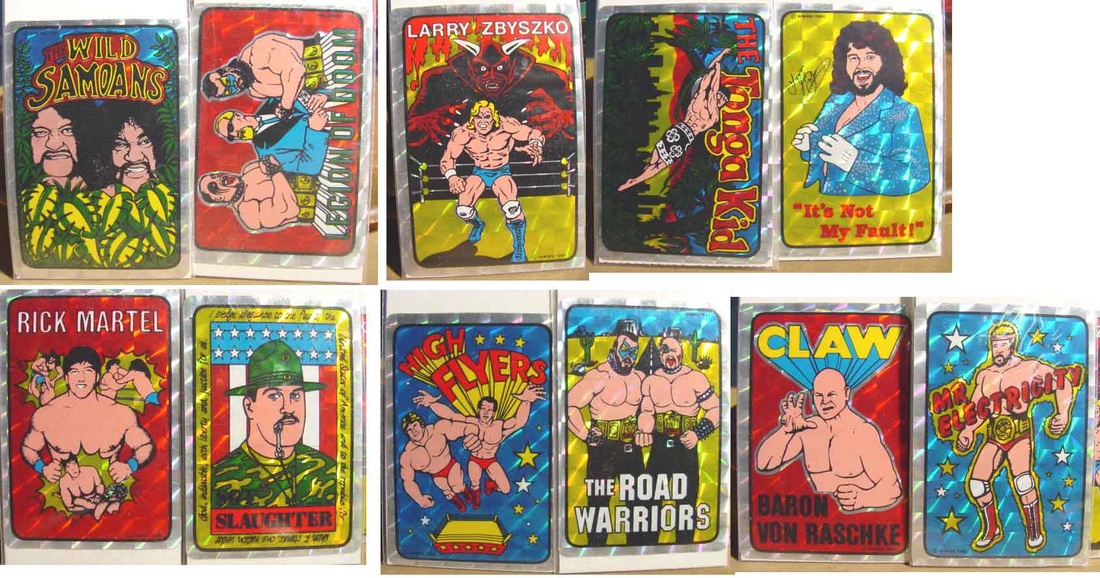

The AWA had a strong business peak from 1969 through 1975. Gagne kept himself world champion during that entire period, although he worked only a few dates per month. But with a crew built around Crusher, Wahoo McDaniel, Superstar Billy Graham, Billy Robinson, Dick Murdoch, Dusty Rhodes, Baron Von Raschke, Ivan Koloff, The Vachon Brothers, Larry Hennig, Red Bastien, Don Muraco as well as the team of Stevens & Nick Bockwinkel, they had a great mix of different types of charismatic performers.

Between 1970 and 1985, they ran six stadium shows in Chicago, often with the theme of a Gagne singles match for the title and a Bruiser & Crusher cage matches often for the tag team titles. In 1970, they drew 21,000 fans and a $148,000 gate, which set the U.S. record at the time, for Bruiser & Crusher vs. Mad Dog & Butcher Vachon in a cage and Gagne defending his title against Von Raschke. In 1972, it was Bruiser & Crusher vs. Blackjacks Lanza & Mulligan in the cage and Gagne defending against Koloff.

In 1974, they did 22,000 fans with Gagne vs. Robinson, The Sheik & Bobby Heenan vs. Bruiser & Brazil, and Crusher & Hennig & Ivan Putski vs. Stevens & Bockwinkel & Graham. In 1976, it was Bruiser & Crusher vs. Lanza & Bobby Duncum in a cage, and Bockwinkel vs. Andre the Giant for the AWA title. In 1980, it was Gagne’s final title win over Bockwinkel, plus a Battle Royal, Bruiser vs. Jerry Blackwell and Crusher & Mad Dog vs. Adrian Adonis & Jesse Ventura.

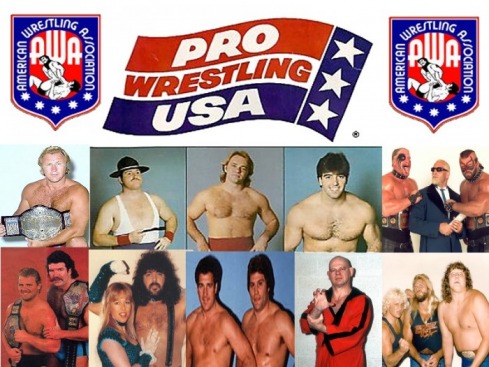

The most loaded show came when they were battling WWF, and on September 28, 1985, drew 21,000 fans paying $288,000 for a 13-match show that Ric Flair vs. Magnum T.A. for the NWA title, Rick Martel vs. Stan Hansen for the AWA title, Ivan & Nikita Koloff & Krusher Khrushchev vs. Crusher & Bruiser & Von Raschke for the NWA six-man titles, Greg Gagne & Scott Hall & Curt Hennig vs. Stevens & Bockwinkel & Larry Zbyszko, Road Warriors vs. Terry Gordy & Michael Hayes for the AWA tag titles, Jerry Blackwell vs. Kamala in a bodyslam match, Kerry Von Erich vs. Jimmy Garvin for the Texas title, Sherri Martel vs. Candi Divine for the women’s title, Steve Regal (not William Regal but a different wrestler) vs. Brad Rheingans for the jr. heavyweight title, Sherri Martel vs. Candi Divine for the women’s title, Giant Baba & Jumbo Tsuruta & Genichiro Tenryu vs. Harley Race & Bill & Scott Irwin, Mil Mascaras vs. Buddy Roberts for the IWA title and Sgt. Slaughter vs Boris Zhukov for the Americas title.

Between 1970 and 1985, they ran six stadium shows in Chicago, often with the theme of a Gagne singles match for the title and a Bruiser & Crusher cage matches often for the tag team titles. In 1970, they drew 21,000 fans and a $148,000 gate, which set the U.S. record at the time, for Bruiser & Crusher vs. Mad Dog & Butcher Vachon in a cage and Gagne defending his title against Von Raschke. In 1972, it was Bruiser & Crusher vs. Blackjacks Lanza & Mulligan in the cage and Gagne defending against Koloff.

In 1974, they did 22,000 fans with Gagne vs. Robinson, The Sheik & Bobby Heenan vs. Bruiser & Brazil, and Crusher & Hennig & Ivan Putski vs. Stevens & Bockwinkel & Graham. In 1976, it was Bruiser & Crusher vs. Lanza & Bobby Duncum in a cage, and Bockwinkel vs. Andre the Giant for the AWA title. In 1980, it was Gagne’s final title win over Bockwinkel, plus a Battle Royal, Bruiser vs. Jerry Blackwell and Crusher & Mad Dog vs. Adrian Adonis & Jesse Ventura.

The most loaded show came when they were battling WWF, and on September 28, 1985, drew 21,000 fans paying $288,000 for a 13-match show that Ric Flair vs. Magnum T.A. for the NWA title, Rick Martel vs. Stan Hansen for the AWA title, Ivan & Nikita Koloff & Krusher Khrushchev vs. Crusher & Bruiser & Von Raschke for the NWA six-man titles, Greg Gagne & Scott Hall & Curt Hennig vs. Stevens & Bockwinkel & Larry Zbyszko, Road Warriors vs. Terry Gordy & Michael Hayes for the AWA tag titles, Jerry Blackwell vs. Kamala in a bodyslam match, Kerry Von Erich vs. Jimmy Garvin for the Texas title, Sherri Martel vs. Candi Divine for the women’s title, Steve Regal (not William Regal but a different wrestler) vs. Brad Rheingans for the jr. heavyweight title, Sherri Martel vs. Candi Divine for the women’s title, Giant Baba & Jumbo Tsuruta & Genichiro Tenryu vs. Harley Race & Bill & Scott Irwin, Mil Mascaras vs. Buddy Roberts for the IWA title and Sgt. Slaughter vs Boris Zhukov for the Americas title.

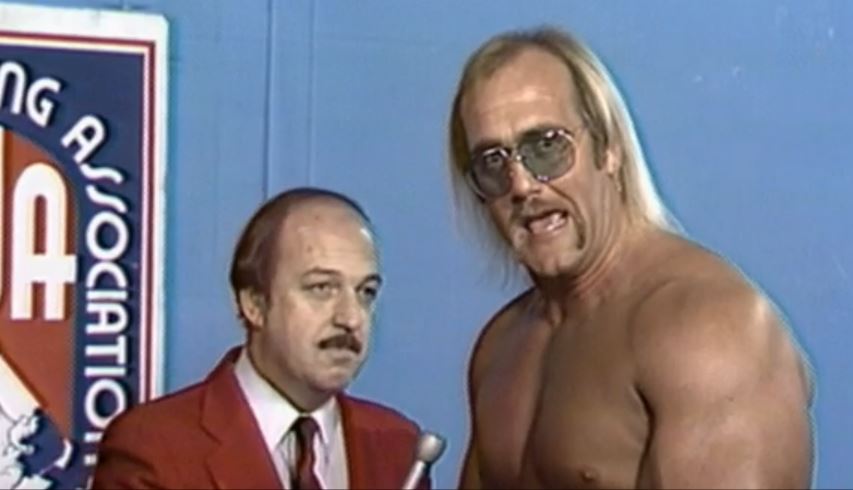

Its second boom, which started in 1981, started with the 56-year-old Gagne’s retirement from the ring, and followed with the emergence of Hulk Hogan as the top babyface. The AWA was so strong that it built up to averaging 8,000 per show in the Twin Cities if Hogan was in Japan, to nearly 16,000 per show when Hogan was headlining.

Hogan had just come off a WWF run where he was a heel managed by Freddie Blassie, who had big matches with the likes of Andre the Giant, Bob Backlund and Tony Atlas. During that period, Vince McMahon Sr., who had a working agreement with New Japan Pro Wrestling, sent Hogan overseas. At first, he went with Blassie, which gave him instant credibility, because Blassie was a huge draw in Japan during the 1960s and the media gravitated toward him.

But Hogan quickly became popular in Japan, and really that’s where the birth of Hulkamania can be traced.

After his WWF run had run its course, Gagne brought him to the AWA as a heel, managed by Luscious Johnny Valiant, who at first did all the talking for him. But seeing the huge muscle man with the tan and blond hair, the AWA fans went wild for him from the start. Gagne immediately flipped him babyface, ditched Valiant, and did an angle where one of his top heels, Blackwell, was destroying Brad Rheingans, when Hogan jumped in and made the save, bodyslamming the supposed 462 pounder.

Hulkamania was born. Coming out to “Eye of the Tiger,” and with interview coaching from Gagne, that became the AWA’s golden era.

Hogan had just come off a WWF run where he was a heel managed by Freddie Blassie, who had big matches with the likes of Andre the Giant, Bob Backlund and Tony Atlas. During that period, Vince McMahon Sr., who had a working agreement with New Japan Pro Wrestling, sent Hogan overseas. At first, he went with Blassie, which gave him instant credibility, because Blassie was a huge draw in Japan during the 1960s and the media gravitated toward him.

But Hogan quickly became popular in Japan, and really that’s where the birth of Hulkamania can be traced.

After his WWF run had run its course, Gagne brought him to the AWA as a heel, managed by Luscious Johnny Valiant, who at first did all the talking for him. But seeing the huge muscle man with the tan and blond hair, the AWA fans went wild for him from the start. Gagne immediately flipped him babyface, ditched Valiant, and did an angle where one of his top heels, Blackwell, was destroying Brad Rheingans, when Hogan jumped in and made the save, bodyslamming the supposed 462 pounder.

Hulkamania was born. Coming out to “Eye of the Tiger,” and with interview coaching from Gagne, that became the AWA’s golden era.

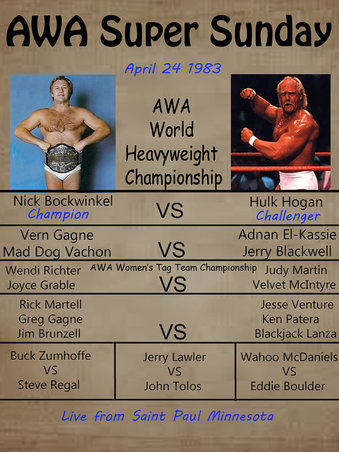

The biggest AWA show of the era was on April 24, 1983, billed as “Super Sunday,” a name taken from the Super Bowl nickname. They not only sold out the 18,000 seat St. Paul Civic Center, but drew another 5,000 closed circuit next door for a double main event, where Gagne came out of retirement once again (this was his second coming out of retirement match in the Twin Cities) to team with Vachon to beat The Sheiks, although the big draw was Hogan getting a title shot at Bockwinkel.

The total gate was $300,000, at the time one of the largest ever in North America. They did the gimmick where Hogan threw Bockwinkel over the top rope while the ref was down, but came back to pin Bockwinkel after a legdrop. But Stanley Blackburn overturned the decision and awarded the match to Bockwinkel via DQ. Having the heels lose the title and later having Blackburn overturn the decision for a very legitimate, but frustrating call, had been part of the AWA playbook for years.

The total gate was $300,000, at the time one of the largest ever in North America. They did the gimmick where Hogan threw Bockwinkel over the top rope while the ref was down, but came back to pin Bockwinkel after a legdrop. But Stanley Blackburn overturned the decision and awarded the match to Bockwinkel via DQ. Having the heels lose the title and later having Blackburn overturn the decision for a very legitimate, but frustrating call, had been part of the AWA playbook for years.

Gagne and Hogan had a weird relationship. Gagne was his mentor, yet at the same time, Hogan, with his huge steroided physique and no sports background, never having even played high school football, went against Gagne’s beliefs of what a top wrestler should be. Most promoters who became wrestlers that were top stars, like Gagne, Leroy McGuirk, Roy Shire or Bill Watts, liked to promote wrestlers like themselves on top. With Gagne, he always promoted himself as the ultimate top star.

But Gagne wasn’t out-of-touch when it came to Hogan. As soon as he saw the crowd flip, he went with it immediately. And when it was working, he pushed Hogan as his top star, to the point he even stopped using Crusher during the summer of 1981, to not confuse the issue over who was the top babyface, claiming Blackwell Crusher and forced him to retire, just weeks before the Hogan turn.

Even though Hogan’s big money was made in Japan, where he earned $10,000 per week, and he was not available full-time, it was very clear Hogan was the company’s biggest star from the first shows after the turn. He never beat Hogan. Hogan, because of his Japan stardom and the way the press covered wrestling then, was like Bruiser Brody, Stan Hansen and Andre the Giant, where he wasn’t going to lose anyway. But Gagne never pressed the point. During the heyday of Crusher, he very rarely lost and Hogan was booked as the modern version. He didn’t need the title to draw, given that he never won the AWA title.

Still, Gagne was a promoter and he knew that Hogan was the goose that laid the biggest golden eggs he’d ever had.

And then the world changed again.

But Gagne wasn’t out-of-touch when it came to Hogan. As soon as he saw the crowd flip, he went with it immediately. And when it was working, he pushed Hogan as his top star, to the point he even stopped using Crusher during the summer of 1981, to not confuse the issue over who was the top babyface, claiming Blackwell Crusher and forced him to retire, just weeks before the Hogan turn.

Even though Hogan’s big money was made in Japan, where he earned $10,000 per week, and he was not available full-time, it was very clear Hogan was the company’s biggest star from the first shows after the turn. He never beat Hogan. Hogan, because of his Japan stardom and the way the press covered wrestling then, was like Bruiser Brody, Stan Hansen and Andre the Giant, where he wasn’t going to lose anyway. But Gagne never pressed the point. During the heyday of Crusher, he very rarely lost and Hogan was booked as the modern version. He didn’t need the title to draw, given that he never won the AWA title.

Still, Gagne was a promoter and he knew that Hogan was the goose that laid the biggest golden eggs he’d ever had.

And then the world changed again.

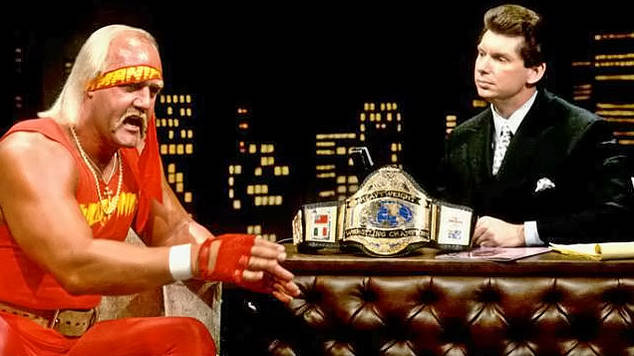

Vince McMahon was looking to expand, and made an offer to buy out Gagne. Gagne felt the number offered was ridiculous, and besides, the last thing he was looking to do was sell when his promotion was producing more revenue than ever before.

McMahon was ambitious and Hogan was going to be given an offer of far more than he made in the AWA and New Japan, because he was the key to McMahon’s goals. Had Hogan been AWA champion, there is no way he’d do the job on the way out. McMahon would have insisted he didn’t given the nature of what the business was then. And Hogan wasn’t doing jobs for anyone anyway.

Historically, Gagne has always been maligned for being so stupid and out of touch for never making Hogan champion. While the decision can certainly be debated, it’s hardly open-and-shut. And while Gagne was clearly out of touch with wrestling when faced with the competition with McMahon, unable or unwilling to up pay and keep top talent, or upgrade his television, his booking of Hogan was an unquestioned success.

For one, Hogan was booked along the lines of Crusher, who did hold the AWA title three times between 1963 and 1965, but never when he really peaked as a draw several years later and when the AWA expanded and became what it was remembered as.

McMahon was ambitious and Hogan was going to be given an offer of far more than he made in the AWA and New Japan, because he was the key to McMahon’s goals. Had Hogan been AWA champion, there is no way he’d do the job on the way out. McMahon would have insisted he didn’t given the nature of what the business was then. And Hogan wasn’t doing jobs for anyone anyway.

Historically, Gagne has always been maligned for being so stupid and out of touch for never making Hogan champion. While the decision can certainly be debated, it’s hardly open-and-shut. And while Gagne was clearly out of touch with wrestling when faced with the competition with McMahon, unable or unwilling to up pay and keep top talent, or upgrade his television, his booking of Hogan was an unquestioned success.

For one, Hogan was booked along the lines of Crusher, who did hold the AWA title three times between 1963 and 1965, but never when he really peaked as a draw several years later and when the AWA expanded and became what it was remembered as.

And Gagne was very willing to make Hogan champion, but there was an issue with Japan. Gagne had a business deal with Giant Baba where the AWA champion, and its top talent, would be booked for All Japan Pro Wrestling. Hogan was under contract to New Japan, and All Japan and New Japan were bitter rivals at the time. Still, that wasn’t enough for Gagne to not use Hogan as his top star. But he’d risk his lucrative Japanese deal if his world champion worked for the opposition. It was an issue Gagne and Hogan tried to work out, but never could make work.

Additionally, Hogan never stopped drawing big in the AWA. He didn’t need the belt to pack houses, and since he wasn’t full-time, you still had Bockwinkel defending against other babyfaces so there were two major matches when he was around, or Bockwinkel’s defenses being able to headline when Hogan wasn’t around. If Hogan’s failure to win the title at Super Sunday was a mistake, it would have been reflected in weaker business. If anything, the core AWA cities were still on the upswing on the shows Hogan appeared on.

And while this didn’t factor into the decision, it would have been disastrous had he made Hogan champion.

Additionally, Hogan never stopped drawing big in the AWA. He didn’t need the belt to pack houses, and since he wasn’t full-time, you still had Bockwinkel defending against other babyfaces so there were two major matches when he was around, or Bockwinkel’s defenses being able to headline when Hogan wasn’t around. If Hogan’s failure to win the title at Super Sunday was a mistake, it would have been reflected in weaker business. If anything, the core AWA cities were still on the upswing on the shows Hogan appeared on.

And while this didn’t factor into the decision, it would have been disastrous had he made Hogan champion.

Hogan was leaving at the end of 1983 under any circumstances. McMahon had the foresight to know that if he wanted to go national, Hogan was clearly the guy to build around.

Jimmy Snuka was unreliable and old. McMahon felt Bob Backlund, the current champion, wasn’t anything like what he wanted. Dusty Rhodes was older, and fat, plus he was booking in the Carolinas but he was exactly the opposite of what McMahon wanted a champion to look like to a new audience.

Kerry Von Erich, probably the other most charismatic babyface, who had the look, was also unreliable and weak on interviews, plus his father had a promotion and it would be difficult to get him. And while Von Erich would have been a major national star with the same spotlight, he probably would have self destructed even if he was willing to leave, and even he didn’t have the kind of potential that Hogan did.

Jimmy Snuka was unreliable and old. McMahon felt Bob Backlund, the current champion, wasn’t anything like what he wanted. Dusty Rhodes was older, and fat, plus he was booking in the Carolinas but he was exactly the opposite of what McMahon wanted a champion to look like to a new audience.

Kerry Von Erich, probably the other most charismatic babyface, who had the look, was also unreliable and weak on interviews, plus his father had a promotion and it would be difficult to get him. And while Von Erich would have been a major national star with the same spotlight, he probably would have self destructed even if he was willing to leave, and even he didn’t have the kind of potential that Hogan did.

As bad as it was for Gagne to lose Hogan, and it was a killer that he never recovered from, it would have been worse to lose Hogan’s drawing power and have the guy his fan base considered the world champion on McMahon’s TV being billed as world champion. Given how wrestling, titles and wins and losses were viewed, it would have crippled the value of the AWA title when they’d have to put it back on Bockwinkel, and everyone knew Hogan had beaten him, never lost, and was on another TV channel as champion.

The AWA did well in 1984 even without Hogan. Crusher was brought back, but he was 57 years old by then and he really wasn’t going to work out past being a short-term nostalgia act. But Gagne brought in people like The Road Warriors, Sgt. Slaughter and Bruiser Brody. While he was losing to McMahon, he had a good year, but things deteriorated rapidly.

The AWA did well in 1984 even without Hogan. Crusher was brought back, but he was 57 years old by then and he really wasn’t going to work out past being a short-term nostalgia act. But Gagne brought in people like The Road Warriors, Sgt. Slaughter and Bruiser Brody. While he was losing to McMahon, he had a good year, but things deteriorated rapidly.

Almost everyone who worked in the AWA wanted to leave and work for Vince McMahon. And McMahon would take anyone.

The wrestling in the AWA wasn’t particularly good during the Hogan era, and the TV was worse. It was shot in a TV studio, with a very simple format. Every match would be a squash match. Angles were rare. The announcing wasn’t good. However, the interviews, with people like Ventura, Bockwinkel and Bobby Heenan, working with Okerlund, was some of the best in the business. The AWA was also by that point an established part of the community, and they were the only wrestling on television in most of their cities. They were behind the times. But it didn’t matter. They were the only game in town.

But when cable hit big, and the WWF got television in their key cities, the AWA TV paled in comparison. Younger fans quickly switched their allegiances to the WWF, since Hogan had been the AWA’s big star for the past several years.

The AWA fell hard, but Gagne did stay in the game longer than he would have due to getting a weekly television deal on the fledgling ESPN. ESPN saw that wrestling was drawing big ratings on TBS and USA, and wanted in. They inked a deal with World Class, but it would be to air old shows since World Class was making more money with its shows first-run through national syndication.

It came down to the AWA and Mid South Wrestling. Mid South was producing arguably the best television in the country, and its territory was hot. But the AWA got the nod, largely because ESPN executives knew who Sgt. Slaughter was, and didn’t know anyone on the Mid South roster.

The wrestling in the AWA wasn’t particularly good during the Hogan era, and the TV was worse. It was shot in a TV studio, with a very simple format. Every match would be a squash match. Angles were rare. The announcing wasn’t good. However, the interviews, with people like Ventura, Bockwinkel and Bobby Heenan, working with Okerlund, was some of the best in the business. The AWA was also by that point an established part of the community, and they were the only wrestling on television in most of their cities. They were behind the times. But it didn’t matter. They were the only game in town.

But when cable hit big, and the WWF got television in their key cities, the AWA TV paled in comparison. Younger fans quickly switched their allegiances to the WWF, since Hogan had been the AWA’s big star for the past several years.

The AWA fell hard, but Gagne did stay in the game longer than he would have due to getting a weekly television deal on the fledgling ESPN. ESPN saw that wrestling was drawing big ratings on TBS and USA, and wanted in. They inked a deal with World Class, but it would be to air old shows since World Class was making more money with its shows first-run through national syndication.

It came down to the AWA and Mid South Wrestling. Mid South was producing arguably the best television in the country, and its territory was hot. But the AWA got the nod, largely because ESPN executives knew who Sgt. Slaughter was, and didn’t know anyone on the Mid South roster.

The AWA went on for several more years, with crowds dwindling everywhere. Still, they had some of the best young talent in wrestling, most notably Curt Hennig and Shawn Michaels. Bockwinkel and Hennig did a 60 minute draw at a TV taping, which aired on New Year’s Eve in 1985 on ESPN and was one of the best matches of that era. While Bockwinkel retained the title, it was the match that really made Hennig, who hit his stride even bigger when he went heel and got the AWA title. Michaels and partner Marty Jannetty had great matches, most notably a television bloodbath, against Buddy Rose & Doug Somers. Paul Heyman first made his national name as Paul E. Dangerously, managing tag team champions Pat Tanaka & Paul Diamond and the Original Midnight Express of Dennis Condrey & Randy Rose.

But soon Gagne gave up the ghost, as he could no longer promote profitable house shows. He survived based on the ESPN deal, and just putting his own money into the promotion. An attempt at PPV built around Jerry Lawler vs. Kerry Von Erich to unify the AWA title (which Lawler had beaten Hennig for) and the World Class title, did poorly and was never tried again. When Gagne ran out of money, and ratings dropped to where ESPN no longer had interest in broadcasting wrestling, the AWA limped to its death in 1991.

But soon Gagne gave up the ghost, as he could no longer promote profitable house shows. He survived based on the ESPN deal, and just putting his own money into the promotion. An attempt at PPV built around Jerry Lawler vs. Kerry Von Erich to unify the AWA title (which Lawler had beaten Hennig for) and the World Class title, did poorly and was never tried again. When Gagne ran out of money, and ratings dropped to where ESPN no longer had interest in broadcasting wrestling, the AWA limped to its death in 1991.